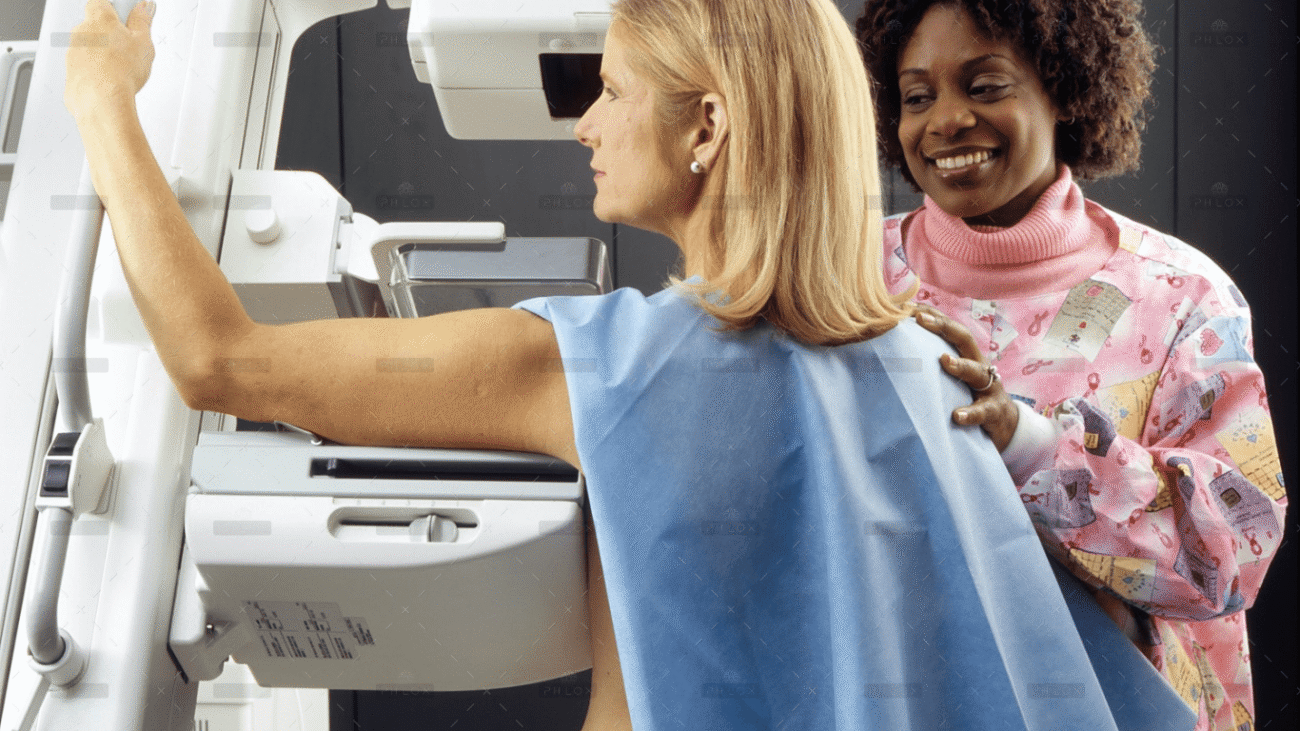

Health isn’t just about treating illness—it’s about preventing it. Many people visit the doctor only when they feel unwell, but regular health checkups are essential for early detection and long-term wellness. Taking time for routine screenings can save you from major health issues later on.

1. Early Detection Saves Lives

Regular checkups help identify health problems at an early stage when they’re most treatable. Conditions like high blood pressure, diabetes, or even cancer often show no symptoms until they’ve progressed. A simple test could make a life-changing difference.

2. Track Your Health Progress

Routine visits allow you and your doctor to track important health indicators like blood pressure, cholesterol levels, weight, and more. This helps in adjusting lifestyle habits or treatment plans before any serious condition develops.

3. Preventive Care Guidance

Doctors provide valuable advice on diet, exercise, stress management, and other preventive measures during checkups. They can also recommend age-appropriate screenings or vaccinations based on your health history.

4. Peace of Mind

Knowing you’re in good health can reduce stress and anxiety. Regular checkups build confidence and trust in your well-being, allowing you to focus more on life and less on worry.

5. Strengthens Patient-Doctor Relationship

Frequent check-ins help build a lasting relationship with your doctor. They become familiar with your health patterns, which leads to better, more personalized care over time.

In Conclusion

Your health deserves consistent attention—not just when you’re sick. Regular checkups are a simple yet powerful way to take control of your health, prevent serious conditions, and enjoy a better quality of life. Schedule your next visit today—because prevention is always better than cure.